Matching Process to Design

Commissioned article published in Ceramics Monthly Feb 2016 about the process of working with manufacturers and subcontracters, factories and collaborators.

“Things come to matter through our intimate relations with them, object and subject combined and entwined, inseparable in mind and memory.”— Crewe, 2011

Industrially produced ceramics, everyday ceramics perhaps, can be a useful tool to engage communities. Within our daily lives we encounter a variety of objects, from our cup full of hot tea in the morning, to a table laden with Sunday dinner delights, all presented on the humble plate; these objects are within our collective, (if perhaps Western) consciousness. Ceramic objects in this format contain many associations and can be intrinsic in forming and recalling memories of people, place, or experience. They can enable us to create our own narrative of the world around us. As a somewhat common language, I have used their accessibility to establish conversations and connections with different parts of the UK community, enabling individuals to create personal and group narratives on a public level (in particular through Graffiti*d 2009 and Wesley Meets Art 2008).

Craft and Industry Collaborations

Craft and industry have a plethora of overlaps, and working together can provide insights and shifts of perspective that can resolve issues or simply move production into a new area—for either party. Successful partnerships are those which are clear in their goals—ones in which both parties gain. They are also not always straightforward collaborations—there are many ways to work with others. Programs such as the British Ceramics Biennial, which combines exhibitions with conferences, symposia, and special projects provide such opportunities for partnerships and collaborations to form between individual makers and industry.

One example is the artist-into-industry type of residency. This allows both ceramic artists and artists from other media to complete specific projects in the factory setting, often times with resources and technical expertise made available to the artist. The artist Andrea Walsh undertook a residency at Wedgwood in 2009, where she was artist in residence for six months at the Barlaston factory. Having trained in fine art and glass, Based with the model makers of the factory, she explored themes of the Minton brand of Wedgwood—experimentation, opulence and luxury—responding to this within a new body of work that continues to be central to her practice to date. Key to her experience was the idea of working with others—learning from the hugely experienced and talented people working within Wedgwood has inspired her practice in many ways. “The project was self directed, and therefore enabled a freedom to explore and investigate the many aspects of the ceramics industry in relation to my own work,” Walsh explains (1). The experience of having an artist in residence can benefit the company in many ways—the artist in residence, has time to investigate in a way that staff on a commercial deadline just don’t have the time for. New insights can be made visible into existing archives, or with materials and techniques, which can allow the company to revalue their own products. It can also open up new product lines, techniques, materials, and processes; sometimes an external perspective is all that is needed to see the small shifts that can be made to existing processes to improve efficiency or alter the product outcome. Residencies are one way of exploring this common ground, but there are others—developing new products, research projects, and archive exploration can provide insight and new future paths. Perhaps small-scale production houses have an opportunity here too, both in working with individual makers in a similar way, but also to work with large-scale industry to evaluate among other things, scales of production, and the associated benefits and pitfalls. Sharing of experience and passing on knowledge is something that ceramic makers have always been good at.

Industrial Water-Jet Cutting

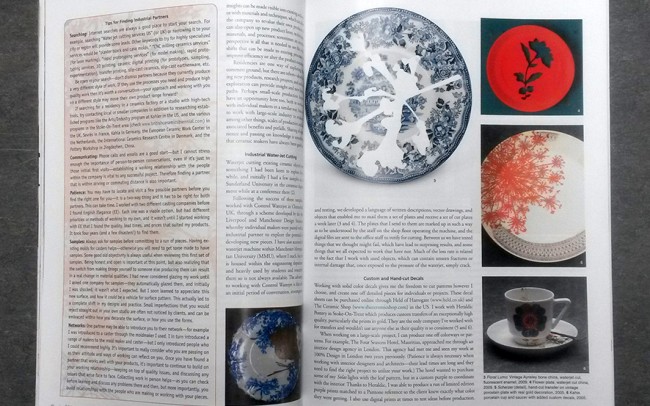

Initially I had a few samples cut at Sunderland University in the ceramics department while at a conference there (2). Following the success of these samples I worked with Control Waterjet in Chesterfield, UK, through a plan developed by the then Design Initiative, in Manchester, whereby individual makers were paired with an industrial partner to explore the potential for developing new pieces. I have also accessed the waterjet cutting machine within Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU), where I teach, but this is housed within the engineering department and heavily used by students and researchers in that department so is not always available. The advantage to working with Control Waterjet is that after an initial period of conversation, investigation, and testing, we developed a language of both word, vector drawings, and objects that enabled me to mail them a set of plates and receive a set of cut plates back a week later (3–4). The plates that I send to them are marked up in such a way as to be understood by the staff on the shop floor operating the machine, and the digital files are sent to the office staff to verify for cutting. Between us we have tested things that we thought might fail, which have lead to surprising results, and some things that we all expected to work that have not! Much of the loss rate is to do with the fact that I work with used objects, which contain unseen fractures or internal damage that once exposed to the pressure of the waterjet simply crack.

Custom and Hand-cut Decals

Working with solid color decals gives me the freedom to cut patterns however I choose, and create one off detailed pieces for individuals or projects. These can be purchased online through Held of Harrogate (www.held.co.uk) and The Ceramic Shop in the US. I work with Heraldic Pottery in Stoke-On-Trent to produce my transfers, which are of an exceptionally high quality, particularly the custom prints in gold are exquisite. They are the only company I’ve worked with for transfers and wouldn’t use anyone else as their quality is so consistent (5–6). When working on a large-scale project I can produce one off colorways or patterns. For example, The Four Seasons Hotel, Mauritius, approached me through an interior design agency in London. This agency had met me and seen my work at 100% Design in London two years previously. (Patience is always necessary when working with interior designers and architects—their lead times are long and they need to find the right project to utilize your work!) The hotel wanted to purchase some of my Solas lights with the leaf pattern, but in a custom purple to coordinate with the interior. This was no problem for Heraldic, and I was able to produce a run of limited edition purple prints matched to a Pantone reference so the client knew exactly what color they were getting. I also use digital prints at times to produce four-color prints, or to test ideas before production. Given the choice however, I always opt for screen-printed transfers as the qualities from these are much crisper than the digital prints. My first love though is hand cutting transfers—there is something infinitely satisfying about the process!

Although there are less companies around of the medium sized studio of English Elegance, there are more and more individual studio artists that are producing work for other artists as part of their practice.

The Solas lighting range (7–8) was produced (no longer in production) by English Elegance in Congleton, UK. This was an amazing family studio, producing a range of wares for individual designers, shops, and larger distributors. They were expert at resolving issues and were incredibly supportive to me during the seven years of production. Again, the relationship we established was so important to the quality of the end product—their understanding of my market helped to form clear quality control levels and establish a good working basis. Each piece was pierced by hand both before and after glazing. An incredibly time consuming process, each was done with such care and attention. When I was working on a large scale commission for Andor Technology in Belfast, Northern Ireland, I needed to pierce individual star constellations into 14 of the 52 lights, and, once they were cast for me, I was allowed to come into the workshop and pierce each one—taking up half of a casting bench for 3 days. The owner, Mike Wood, was incredibly accommodating, and due to the good working relationship we had, I was able to simply ask if I could have some space to pierce, and he was able to work round this with production. The space in the studio was very well organized and although small, incredibly efficient—I was in the corner so as not to get in anyone’s way (7).

Managing Obstacles and Expectations

Often we expect an industrial partner to be able to produce things quickly and cheaply. Often this is the case, but only after the initial testing, quality control, and mold set-up period has been established. It’s important to bear this in mind—expecting a batch of 20 pieces from an initial sketch within two weeks is entirely unrealistic. Particularly with slip casting, the mold is the most important part, the quality of this will determine the quality of the final piece so getting this right is vital! Investing in these models, molds, and initial batches is a real financial outlay, but it is so worth it in the long run. It’s also important to take this into account when pricing. Your individual unit cost may be $10 but once you add on the cost of the model, block, case, and molds, as well as loss rate and VAT/sales tax, this may end up more like $20 over a run of 200 units. Again, bear this in mind when working with a partner, it’s not always the right path. If you want a batch of 20, then it’s probably better if you can work up to this yourself, if it’s 50 then investing in professionally produced molds is well worth it. If it’s 100 or more then working with an industrial partner is the right decision!

Alterations can be necessary to get your product onto the casting bench—if possible, it’s useful to discuss issues of efficiency with both the caster and the mold maker before the model, block, and case are made.

Don’t be impatient—calling a studio one day and not hearing back for a couple of days is common—they are just busy. I’ve heard some horror stories over the years of makers who are demanding and threatening when it comes to payment of invoices, holding the studio hostage to an unrealistic deadline in order to get paid. This does not bode well for your reputation. The ceramics world is a small one with tight networks, and word gets around. If you do run into problems though, don’t be afraid to walk away and find a new partner. If you can’t resolve issues, or communication breaks down, then it is obviously not working—keep everything on a good level from your perspective, and simply write a letter to say you are going to be moving your business elsewhere—and ask them to call to arrange for you to collect your molds and any remaining pieces. If there is no reply to this then visit in person.

My recommendation to students is always, “If you don’t ask, you don’t get,” but that also comes with a good dose of artist and graphic designer Anthony Burrill’s motto, “Work hard and be nice to people.” It goes a long way! The value is in the relationships you establish with the people you work with. If these aren’t well formed you may not be able to maintain a business—however successful your product is.

Finding Partners On Location: The Dhal ni Pol Project

In 2010 I had the opportunity to travel to India, and to work in the Arts Reverie residency and on The Dhal ni Pol project, with several colleagues. The Dhal ni Pol project was incredibly influential on my practice—and has established a focus on narrative that was not there before. Working with Deepak Tahilani, the Laxmi ceramics factory, and the children of the neighborhood to produce teacups with customized narrative decals were integral parts of my project there (9–10). The tunnel kiln at Laxmi was fascinating to work with as it was just so fast (11). Loading pieces at one end and collecting them not long after at the other was just incredible. Unfortunately, given the physical distance I can’t see how this relationship can move forward unless I were to revisit India for a longer period.

Tips for Finding industrial Partners

Searching: Internet searches are always a good place to start your search. For example, searching “Water jet cutting services US” (or UK) or narrowing it to your city or region will provide some leads. Other keywords to try for high-tech services would be “plaster block and case molds,” “CNC milling ceramics services” (for laser marking), “rapid prototyping services” (for model making)

Be open in your search—don’t dismiss partners because they currently produce a very different style of work. If they use the processes you need and produce high quality work then it’s worth a conversation—your approach and working with you on a different style may move their own product range forward!

If searching for a residency in a ceramics factory or a studio with high-tech tools, try contacting local or smaller companies in addition to researching established programs like the Arts/Industry program at Kohler in the US, and the various programs in the Stoke-On-Trent area (check www.britishceramicsbiennial.com) in the UK, Sevrés in France, Kahla in Germany, the European Ceramic Work Center in the Netherlands, and the Pottery Workshop in Jingdezhen, China.

Communicating: Phone calls and emails are a good start—but I cannot stress enough the importance of person-to-person conversations, even if it’s just in those initial first visits—establishing a working relationship with the people within the company is vital to any successful working relationship. Therefore finding a partner that is within driving or commuting distance is also important.

Patience: You may have to locate and visit a few possible partners before you find the right one for you—it is a two-way thing and it has to be right for both partners. This can take time! I worked with two different casting companies before I found English Elegance (EE). Each one was a viable option, but had different priorities or methods of working to my own, and it wasn’t until I started working with EE that I found the quality, lead times, and prices that suited my products. It took four years to find them!

Samples: Always ask for samples before committing to a run of pieces. Having existing molds for casters helps—otherwise you will need to get some made to have samples. Some good old objectivity is always useful when reviewing this first set of samples. Being honest and open is important at this point, but also realizing that the switch from making things yourself to someone else producing them can be a real change in material qualities. I had never considered glazing my work until I asked one company for samples—they automatically glazed them, and initially I was shocked, it wasn’t what I expected! But I soon learnt to appreciate this new surface, and how it could be a vehicle for surface pattern. Small imperfections that you would reject straight out in your own studio are often not noticed by clients, and can be embraced within how you decorate the surface, or how you use the forms.

Networks: One partner may be able to introduce you to their network—for example I was introduced to a caster through the moldmaker I used. I in turn introduced a range of makers to the mold maker and caster—but I only introduced people who I could recommend highly. It’s important to really consider who you are passing on as their attitude and ways of working can reflect on you. Once you have found a partner that works well with your products, it’s important to continue to build on your working relationship—keeping on top of quality issues, and discussing any issues that arise face to face is always important. Collecting work in person helps—as you can check before leaving and discuss any problems there and then.

Resources

Although there are less companies around of the medium sized studio of English Elegance, there are more and more individual studio artists that are producing work for other artists as part of their practice.

Model, Moldmaking, and Slip Casting

- Kiss Me Kate ceramics produces molds, batch, and one off commissions. http://kissmekateceramics.co.uk

- Helen Johannessen of Yoyo Ceramics is a trained ceramist with particular expertise in modelling and mold making, also based in London she too produces molds, models, batch and one off casts. www.yoyoceramics.co.uk

- Mudshark Studios mudsharkstudios.com

- Petro Mold Company www.custommolds.net

- An exceptional resource for ceramics is Anthony Quinn’s Ceramic Design Course book which has a list of useful references for further research.

Decals

- Art Decal Corp. www.artdecalcorp.com (custom decals)

- Bel Decal www.beldecal.com (custom decals)

- Ceramic Decal Printing ceramicdecalprinting.com (custom decals)

- The Ceramic Shop www.theceramicshop.com (custom and solid-color, full-sheet decals)

- Chinese Clay Art www.chineseclayart.com (solid-color, full sheet decals)

- Decal Craft (Canada) decalcraft.com custom decals

- Heraldic Pottery (UK) www.heraldicpottery.co.uk (custom decals, digital and screen print)

- Held of Harrogate (UK) www.held.co.uk (custom and solidcolor, full-sheet decals)

- Trinity Decals instardecals.com (custom decals)